TCP sequence number and 3-way handshake

One challenge of TCP is to handle stale packets. Packets from previous connections may get delayed in the network and interfere with new connections. To solve this problem, TCP enforces the following rule on sequence numbers.

Between 2 TCP sockets, only one outstanding sequence number could exist in the network.

We only consider unidirectional traffic here to simplify the discussion. The rule could be stated more specifically as:

Let T be the maximum network round trip delay, any sequence number can be used at most once during T for all connections between 2 sockets.

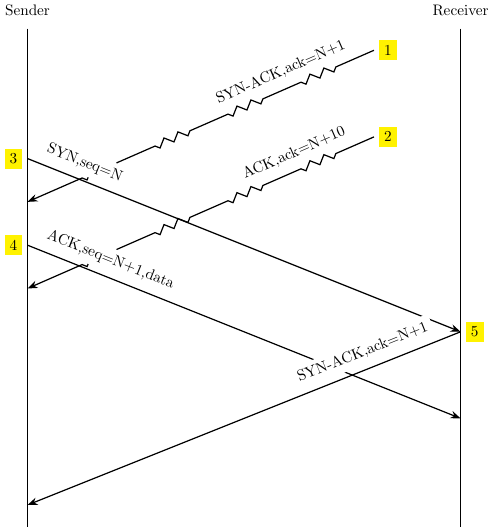

T is limited by packet ttl and network topology. The default value for T is 120 seconds according to Tanenbaum. If this rule is violated, bad things could happen. The following figure shows one such scenario.

Packets 1 and 2 are stale packets from a previous connection. The sender re-uses initial sequence number N in packet 3, before the stale packets are gone. The sender completes 3-way handshake and sends data in packet 4. When the sender receives packet 2, it falsely assumes that 9 bytes are delivered to the receiver.

I am not sure how the sequence number rule is implemented in practice.

RFC 793 recommends using a persistent clock counter that increments about every 4 microseconds. This method is subject to sequence prediction attack and is not used anymore.

Linux computes initial sequence numbers by adding a per-boot random number to a persistent clock counter. This random number could decrease after reboots, so the resulting sequence numbers could decrease, and potentially break the above rule. See the following section for details of Linux sequence number implementation.

As a side note, TCP connections use random ephemeral ports for source ports. It's rare that multiple connections happen between 2 TCP sockets during a short time period. However, TCP dost not prevent a user from specifying a fixed source port for all connections. The randomness of ports is not a requirement of TCP.

3-way handshake

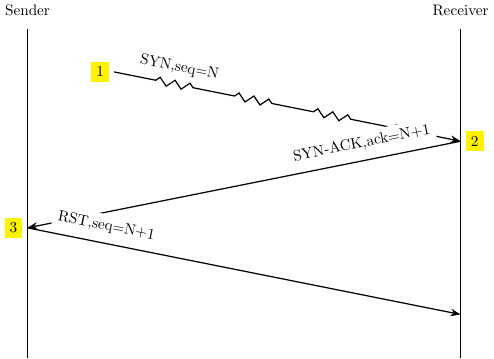

Assume the sequence number rule is satisfied, there's still one problem. When a host receives a SYN packet, it needs to figure out whether this packet is stale or not, then it could discard the stale SYN packet without setting up a connection. The 3-way handshake is designed to help validate SYN packets. For example, in the following figure, the stale SYN packet 1 could not complete 3-way handshake because of the RST packet 3.

Can we attach data in the first SYN or SYN-ACK packets to reduce the connection time? Theoretically yes according to Tomlinson. However, an application cannot accept outstanding data until completion of the handshake. There are several problems with this, for example, SYN flood attack.

Initial Sequence Number in Linux

In Linux the initial sequence number for a TCP connection is computed

by function secure_tcp_seq().

u32 secure_tcp_seq(__be32 saddr, __be32 daddr,

__be16 sport, __be16 dport)

{

u32 hash;

net_secret_init();

hash = siphash_3u32((__force u32)saddr, (__force u32)daddr,

(__force u32)sport << 16 | (__force u32)dport,

&net_secret);

return seq_scale(hash);

}

static __always_inline void net_secret_init(void)

{

net_get_random_once(&net_secret, sizeof(net_secret));

}

static u32 seq_scale(u32 seq)

{

/*

* As close as possible to RFC 793, which

* suggests using a 250 kHz clock.

* Further reading shows this assumes 2 Mb/s networks.

* For 10 Mb/s Ethernet, a 1 MHz clock is appropriate.

* For 10 Gb/s Ethernet, a 1 GHz clock should be ok, but

* we also need to limit the resolution so that the u32 seq

* overlaps less than one time per MSL (2 minutes).

* Choosing a clock of 64 ns period is OK. (period of 274 s)

*/

return seq + (ktime_get_real_ns() >> 6);

}

The function secure_tcp_seq() first gets a per-boot random value

net_secret, computes a hash with this random number, and then adds

the hash to a clock counter (ktime_get_real_ns()) to get the initial

sequence number.

During a boot session, the hash for a connection is constant, so the initial sequence number of each connection grows (module 2^32) with time. After reboot, the new hash could be smaller than the old hash, making it possible to re-use a recent sequence number.

It's interesting to understand the calculations in the comments of

function seq_scale(). The basic idea is that the number of bytes

been sent must increase slower than the sequence number increment.

Otherwise, some bytes could be labeled with sequence numbers that are

used in future connections. So for 2 Mbps network speed, the clock

counter needs to grow faster than 2M/8 = 250 kHz.